someone will remember us

I say

even in another time

– Sappho, trans. Anne Carson

In the last decade or so, the prevailing discourse about lesbian culture and lesbian spaces has centered around the concept of disappearance. The recent closure of some of the oldest lesbian bars across the country (The Oxwood Inn in LA, The Lexington Club in San Fransisco, Hershee Bar in Norfolk) is often understood as both a symptom and a cause of this cultural disappearance, as these spaces have long served as safe havens and as catalysts for community building. For an older generation of lesbians, this loss feels acute, but for younger queer women it may not even register as a loss, as these lesbian cultural touchstones of the 20th century are now often seen as uncool or outdated. This generational dissonance indicates that there has been a lack of sustained conversation between generations of queer women, and that cultural knowledge has not been passed along – in either direction.

With this chapter I hope to diminish this gap by investigating lesbian spaces of the 20th century not simply for how they might have failed (both financially and in their apparent inability to connect across generations), but for how they functioned as cultural safe spaces. In doing so, I will illustrate what lesbian culture may have looked like in the second half of the 20th century in order to connect these cultural moments to current developments in queer female culture and space today. In particular, I am interested in how we might conceptualize the four lesbian cultural touchstones I will be looking at – lesbian pulp novels, lesbian bars, feminist bookstores, and women’s music festivals – in terms of fandom, particularly as it relates to queer female fandom today. I have chosen to frame these cultural moments using the lens of fandom because I have found through my research that media, and queer women’s collective relationship to it, has been a through-line in these communities across time. In fact, this chapter was partially inspired by two older lesbians I interviewed who compared ClexaCon (the focus of Chapter 3) to the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival. By making these connections, I hope to illustrate the long-standing centrality of media within queer cultures, as well the different strategies queer women have taken and continue to take to create and maintain cultural spaces.

This chapter also serves as a means to contextualize the next two chapters of this project, which will focus on examples of queer female communities online as well as the queer female fan convention ClexaCon, placing these moments within a lineage of queer cultural productions. I also intend for this project to serve as an archive of lesbian and queer women’s culture and history, following Anne Cvetkovich’s (2002, 2003) recognition that queer archives are essential in maintaining both our cultural and institutional memory. I will be looking at the four moments/spaces in lesbian history that I outlined above because they represent four significant moments of community building for lesbians, and because they illustrate the importance of media and cultural spaces in building these communities. To conclude this chapter, I will go into some of the reasons that have been proposed to explain the purported disappearance of this culture and these spaces, and interrogate how these changes may have contributed to the queer culture that exists today.

1950-1965: Lesbian Pulp Novels

The first case study I will be looking at is not a physical space, but rather a particular media text that had an effect on the spaces that were imagined for queer women: lesbian pulp novels. Lesbian pulp novels had their heyday in the 1950s and early 1960s, a period during which “more lesbian novels were published […] than at any other time in history” (Zimmerman 9). These cheap paperback books are known for their titillating covers, and were often written by men for a male audience. However, as Yvonne Keller (2005) notes, there was a distinct subset of these novels during this period that were written by women, and that quickly gained a dedicated female audience. Keller calls these pulps “pro-lesbian,” and estimates that at least 90 of the 500 novels published during this period fall into this category. However, although there were some more “affirming” lesbian pulp novels that existed during this time, lesbians voraciously consumed these novels regardless of quality. Joan Nestle has called these novels “survival literature,” as they were “coveted and treasured for their sometimes positive and sometimes awful but decidedly lesbian and decidedly available representation” (Keller 386).

Keller goes on to suggest that lesbian pulp novels are “important to lesbian studies because their truly impressive quantities helped create the largest generation of self–defined lesbians up to that point (387),” a generation of women who would go on to be involved in the first national gay rights movement of the late 1960s and 1970s. Lesbian pulps allowed lesbians to see themselves represented, confirming that they did in fact exist, and opened up the possibility that there were others out there like them. As Linnea Stenson puts it:

The emancipatory potential of pulp novels lie not simply in their storylines or covers, but rather in the cultural practice of consuming them, which allowed lesbians an opportunity (within an otherwise rigidly heteronormative system of representation) to re-imagine themselves and the world around them (46).

These pulp novels greatly affected the lesbian imaginary, allowing lesbians to finally envision a space for themselves in the cultural sphere. However, the imagined space that opened up as a result of these novels was limited – the characters in these books were almost exclusively white, leaving lesbians of color out of this cultural imaginary (Keller). Despite this, lesbian pulp novels were still consumed by lesbians of color, as there was little else in the way of sapphic media available at the time.

In addition to expanding the space of the lesbian cultural imaginary, these novels in some cases encouraged the formation of physical lesbian spaces. Stenson writes about a lesbian couple from Toronto who packed up and moved to Greenwich Village because they had learned from the pulps that was where lesbians lived (46). Indeed, lesbian pulp novels not only encouraged lesbian self-identification among readers, but also “conveyed a sense of lesbian culture, and sometimes helped lesbians find others like themselves” (Walters 85). Readers of these pulps were made aware of the spaces that lesbian might frequent, thus increasing the profile of spaces such as lesbian bars. In her book Heroic Desire (1998), Sally Munt writes that “nightclubs were a visible site for women interested in ‘seeing’ other women, and it is in this literature of the 1950s and 1960s that the bar becomes consolidated as the symbol of the home” (40). Thus, lesbian pulp novels were significant in lesbian history both because they inspired lesbian self-identification and encouraged lesbians to envision their own cultural spaces. In the next section I will investigate another significant moment in lesbian history during this period: the emergence of lesbian bars.

Lesbian Bars

Over the last decade or so, a peculiar “disappearance” seems to have occurred. Lesbian bars across the country, even the oldest and most prominent bars, have been shutting down. News articles lamenting this loss appear every few months, creating the sense that the disappearance of lesbian bars across the U.S. has become something of an epidemic. The loss of these spaces is likely perceived differently by different populations. For older queer women, this disappearance may feel like a loss of community or a loss of history. For younger queer women, many of whom have never even set foot in a lesbian bar, this disappearance may seem like the regrettable loss of a bygone era, or perhaps even the welcome consequence of a culture that is less caught up in labels. Instead of investigating which of these perspectives holds the most merit, what I intend to do in this section is illustrate how lesbian bars have historically functioned within lesbian culture, as well as investigate the potential reasons for their disappearance. By doing so, I hope to highlight the centrality of lesbian bars among lesbian culture of the past, while also illustrating in subsequent chapters the ways in which young queer women have managed to find community despite their relative absence.

Lesbian bars have a long and storied history in the United States. In her 1992 article “Invisible Women in Invisible Places” Maxine Wolf “traces Lesbian use of bar environments in the U.S. to the late 1800s and the existence of bars used exclusively by Lesbians to the 1920s” (142). Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy and Madeline Davis (2005) suggest that by the 1940s, “gay and lesbian social life became firmly established in bars in most cities in the U.S.” (29). Wolf notes that laws (including anti “cross-dressing” measures and statutes prohibiting sexual acts “against nature”) and the constant threat of violence greatly affected the experience and the physical environment of these spaces, with many lesbian bars lacking the signage or other physical features that would explicitly mark them as lesbian. Up until the 1970s (and even afterward) going to these bars was risky, as patrons were always under threat of violence or exposure. As Wolf puts it, “women who remained in the bar environments in the 50s and 60s had a conscious sense that they were risking a great deal to be there and decided it was worth it” (153).

This issue of safety and risk greatly affected the clientele of these bars during the first few decades of their existence and leads us to an important point – the bars were often segregated, both in terms of class and race. In her study of lesbian bars in Detroit from 1939 to 1965, a period during which there were approximately 20 bars, Roey Thorpe (2005) found that these bars had mostly white clientele and mostly white owners, and that the bars were also segregated by class. According to Thorpe, “Blue collar and white collar lesbians had different ideas and needs when it came to the question of safety” (178). Thorpe argues that for working-class lesbians, safety meant having a “turf,” and having a community that acted as protection when violence arose. On the other hand, middle-class lesbians defined safety as living an acceptable, middle-class life while also developing friendships and relationships with other women in private (Thorpe 175). In addition, Thorpe illustrates, middle-class women with jobs such as teachers or librarians would almost definitely be fired if they were outed, while working-class women who worked in factories would likely face violence if they were outed but could potentially keep their jobs (175).

In their study of lesbian bars in Baltimore during the 1930s and 1940s, Kennedy and Davis (2005) echo these sentiments, noting that because of laws during this period that prevented women from entering bars (in an effort to stop venereal disease), many lesbian bars were located in red-light districts, which further discouraged middle or upper-class women from patronizing them. Upper-class women instead hosted their own private parties, which in turn working-class women were not invited to. Black lesbians in Buffalo during this period, greatly outnumbered at lesbian bars, most often socialize at house parties or at straight black bars. Kennedy and Davis note that due the size of the black population in Buffalo during this time, “the city could not offer anonymity to black lesbians” (67), and thus some traveled to New York City to find community. The specific raced and classed environments of bars during this period gives us insight into who needed these spaces, who had access to them, and how they were used. As Thorpe notes, once lesbian bars became institutionalized community spaces in the 1970s, they gained more middle-class patrons and lost many of the qualities that defined them as working-class spaces in previous decades (179). However, these new patrons also increased their economic viability.

In her study of lesbian bars in Montréal, Julie Podmore (2006) divides the history of these bars into five different eras: The Red-Light Era (1950–1970); The Age of ‘Underground’ (1968–1979); The Golden Age (1982–1992); and The Queer Era (1992–2001). The characteristics of The Red-Light Era most closely align with the bar scenes highlighted above in Detroit and Baltimore, as Montréal had similar laws preventing women from entering bars until 1971. During the Underground era lesbian bars in Montréal moved downtown, and during the Golden Age the bars become more diverse both in terms of physical location and population, thus increasing their popularity. The Queer Era marks the beginning of the decline in popularity of lesbian bars, a decline which has continued since Podmore concluded her study in the early 2000s. Indeed, from 1992 to 2003, the number of lesbian bars in Montréal decreased from 7 to 1, while gay male spaces and mixed-gender spaces proliferated.

Podmore provides several explanations for the disappearance of lesbian spaces in Montréal. One of these explanations is the increasing popularity of a more broadly “queer” culture that emerged in the 1990s. The increasing popularity of queer or mixed-gender spaces meant that lesbian bars could no longer sustain themselves. In addition, economic forces had a role to play. While gay neighborhoods were often gentrified by the gay community itself (ie. the cost of living in these neighborhoods increased as a result of middle-upper class gay men flocking to the area), lesbian spaces thrived in diverse neighborhoods that became gentrified by outside forces. Lastly, it is important to note that in Montréal, as in many other cities, there have always been more gay bars than lesbian bars. As Podmore puts it, “The asymmetries of gender within the formation of ‘community’—queer or otherwise—have an important role to play in the production of identity and space” (618). Thus, it is likely a combination of cultural and economic forces that have lead to the decline of lesbian bars in North America. Indeed, while the dominance of male-centric spaces over female-centric ones is not new, this inequity has had a distinct and lasting effect on queer women and lesbian spaces in particular.

Importantly, the disappearance of lesbian bars in the 21st century also means that queer women of different generations have very different experiences and perspectives in regard to community spaces. Katherine Fobear, in her 2012 study entitled “Beyond A Lesbian Space? An Investigation on The Intergenerational Discourse Surrounding Lesbian Public Social Places in Amsterdam,” has some significant insights about this topic. She focused on several bars in Amsterdam that had to allow gay men and straight women into their spaces in order to keep their doors open. Fobear found that older women felt that lesbian-only spaces had in the past contributed to the feeling of “uniting under a common cause” (732), something that they saw as missing with new generations. On the other hand, Fobear notes that younger women felt like lesbian-only spaces were “too confined to one aesthetic, ideological, and social appeal.” (736).

This intergenerational discourse that Fobear highlights indicates that there is still not a consensus about the necessity of lesbian bars as a community space. While some younger queer women may find lesbian bars old-fashioned or stifling, older women often that these spaces were and are essential to one’s sense of self-acceptance and to community building practices, not to mention the years of history contained within their walls. Podmore suggests we look at these spaces within a historical context:

While in retrospect this practice may seem ‘essentialist’ and limiting, at the time it was seen as necessary to ensure the rare control that these women had over commercial, ‘sexualized’ space. Their women-only status, therefore, was an important territorial strategy that ensured freedom from harassment and voyeurs (612).

For much of their existence, the primary function of lesbian bars was safety, producing territorial practices that today might read as exclusionary. With this historical context in mind, we may begin to consider how notions of safety and inclusion/exclusion are deployed in contemporary iterations of queer community spaces. As Fobear puts it, we may be “caught in the uneasy divide of being beyond having an exclusionary space while at the same time needing a space where [we] are included fully” (743). We will continue to ponder these questions throughout this project, focusing on how safety is often predicated on the notion of exclusivity, and considering how we might utilize the concept of safe spaces in the future.

Feminist Bookstores

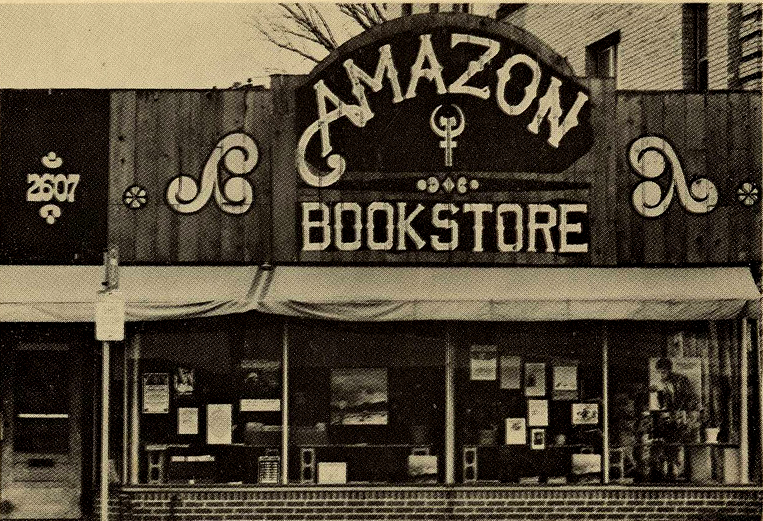

The next space I take as my object of study is also one that largely seems to have “disappeared” from our culture today. Between the 1970s and the 1990s, feminist bookstores acted as lesbian community spaces that both empowered women to learn about lesbian and feminist history while also serving as the meeting places for community events. Kristen Hogan notes that at the height of the movement, there were 130 feminist bookstores across North America, all connected through community newsletters. As of 2020, there are only 10 remaining feminist bookstores in North America, according to this list compiled by Paste Magazine (three of stores on the list have closed since this list was first published). The disappearance of feminist bookstores likely has a lot do with the forces of capitalism and the increasing power of corporations like Amazon (who famously got into a legal battle with the lesbian-owned Amazon Bookstore Cooperative), as well as the decline in popularity of second-wave feminist and lesbian feminist ideologies and practices. With this section, I again want to explore the importance of feminist bookstores to the lesbian community in the 20th century, as well as the connection between media, identity, and community building.

In her book The Feminist Bookstore Movement: Lesbian Antiracism and Feminist Accountability (2016), Kristen Hogan notes that feminist bookstores had several different functions for lesbians and feminists. She suggests that for bookwomen themselves, feminist bookstores constituted a networked community where bookwomen communicated with one another through writings, newsletters, and events, attempting to hold one another accountable to the ethical standards that they preached. For bookstore patrons, feminist bookstores served as a destination for lesbian travelers, or as a refuge for those in need of support or escape. In addition, through the support of the Feminist Bookstore Network and the Feminist Press, the bookstores encouraged the publication of feminist and lesbian books by authors such as Audre Lorde and Gloria Anzaldúa. These factors made feminist bookstores unique meeting spaces for lesbians in the late 20th century.

Left: bell hooks and Byllye Avery at Charis, in Atlanta, Georgia, circa 1985. Credit. Top Right: Poets Audre Lorde, Meridel Lesueur & Adrienne Rich. Credit. Bottom Right: Amazon Bookstore in Minneapolis (now closed). Credit.

Because of their status as a retail and archival space (preserving and supplying lesbian texts) as well as an event space, feminist bookstores uniquely exemplify the connection between media and minority community building. Feminist bookstores provided individual support and education in the form of literature, as well as community support in the form of lesbian networks and events. In a 2005 essay, Kathleen Liddle notes that “visiting a feminist bookstore is repeatedly cited as a key event in the coming out process” (157). The location of these bookstores was thus significant, as lesbians without a feminist bookstore in their town may have found it necessary to travel to the nearest bookstore to find this community. The dispersed locality of feminist bookstores illustrates one of the largest differences between lesbian community of this era and that of today. While in the 1970s and 80s lesbians searched for other lesbians locally – or else traveled to a specific lesbian-centric location – now many queer women find support online from others who may live nowhere near them, as lesbian-centric physical spaces have become less prevalent.

Additionally, feminist bookstores were important to lesbians because of the media content housed within them. As I mentioned earlier, feminist bookstores exposed lesbians not only to other local women like them, but also to the writings of lesbians and feminists from throughout history. As Liddle puts it:

Although we could think of feminist bookstores as being comprised of both community and merchandise, in essence the books being sold are part of a dispersed lesbian community. Enfolded in their pages are the voices of a diversity of women – real and fictional – whose words provide comfort, encouragement, and guidance (150).

While one’s personal connection to these formative, canonical lesbian texts might not fall within the popular definition of fandom, it is interesting to note how Liddle’s description of the empowering function of these books might reflect how one would describe, say, watching Emily Fields come out on the teen drama Pretty Little Liars (Freeform, 2010-2017). Indeed, television series like Pretty Little Liars in many ways function for young queer women as “dispersed lesbian community” Liddle describes, while sites such as Tumblr and Twitter may act as the spaces where women gather to talk about these texts. The function of feminist bookstores as a community space as well as a space to purchase or consume particular media in some ways reflects the contemporary function of queer fandom today, though the economic and industrial circumstances of these two modes of community are fairly different. In point of fact, the relationship between lesbian movements and lesbian media with the mainstream remains a strained one throughout all of these examples, which is likely one of the reasons most of these spaces have not been able to sustain themselves. In the last section of this chapter, we will look at another force present in many of these spaces: inclusion and exclusion.

Women’s Music Festivals

The first women’s music festival was held at Sacramento State University in 1973. The first National Women’s Music Festival was held the following year, and the first Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival was held in 1976. At their height, both festivals had around 10,000 attendees. These festivals were conceived as non-hierarchical, intimate and exclusive spaces, which in theory meant that they were safe spaces for women, and in particular, for lesbians. These festivals were, for the most part, rural, affordable (attendees could volunteer to pay their way), free from shame, and also encouraged discussions about social issues in politics. In essence, though the festivals centered on live music, they were also much more than that, acting for some women as a sort of sacred pilgrimage and inspiring sexual, political or spiritual awakenings.

Unfortunately, there is little archival evidence of these festivals, as they were not recorded for safety reasons, and little was known about the festivals to outsiders. (Of course, the relative invisibility of these festivals may have been one of the things that allowed them to act and feel like safe spaces for patrons, a value that doesn’t necessarily align with the focus on visibility in modern queer culture). My intent with this section is to locate women’s music festivals along the continuum of lesbian history, paying close attention to how these festivals functioned as safe spaces through the joint processes of inclusion and exclusion. In doing so, I will illustrate both the importance of safe spaces for marginalized communities, as well as the difficulty of defining the boundaries of a community. While many of the spaces I have discussed bring up issues of inclusivity and exclusivity, in recent years much of this discourse has coalesced around women’s music festivals in particular, likely because they are understood to represent the politics of a bygone era. Whether or not statements like this tell the whole story is something I will investigate in this section.

In her book The Disappearing L: Erasure of Lesbian Spaces and Culture (2016), Bonnie Morris discusses some of the significant cultural events of lesbian culture in the 20th century. The book contains her personal archival material from women’s music festivals since the 1970s, including her observations and interviews with attendees. Morris suggests that these festivals served as moments of awakening and revelation for many lesbians, proving to attendees that there was such a thing as a lesbian community. In Morris’ words:

An important function of feminist concerts and festivals in the mid-1970s was their transmission of once-hidden information about lesbian lives. Such gatherings were visual, auditory proof of what Adrienne Rich called lesbian existence and the lesbian continuum. (118)

As primarily rural spaces, women’s music festivals also allowed women to freely express their gender and sexuality. (This particular locality separates these spaces from lesbian bars and feminist bookstores, which were often located closer to urban centers). As Browne (2011) illustrates, the rural location of these festivals meant that women felt free in their bodies – nudity was common at the festivals – and allowed them to freely engage in sexual encounters without fear of voyeurism. (Security was sometimes employed in order to deter peeping toms). To most attendees, these festivals felt like their own small universes, completely distinct from –rather than reflective of – the real world from which they all came.

In addition to the significance of women’s music festivals as a community space, women also came (and returned) for the music itself. As Morris notes, the “songs and albums” of lesbian musicians were “intrinsically woven into many women’s coming-out experiences and relationships” (31) Furthermore, purchasing lesbian music would allow festival attendees to relive the experience once they were back in the “real world”. As Jill Dolan (2012) puts it, along with being affirming or cathartic, “women’s music was pedagogical in the 1970s” (2017). Music and politics were much more intertwined during this decade in part because, as Dolan suggests, political issues felt urgent during this era. Indeed, music was both socially and politically important to lesbians, as it created both imagined and physical community. In her article “Creating Transgressive Space: The Music of kd lang,” Gill Valentine (1995) demonstrates that lesbian music has the potential to create lesbian space even outside of women’s music festivals. Valentine argues that:

[The] ability of lang’s music to signify a sense of belonging or imagined community amongst lesbians means that when two women catch each other’s eyes in this way, her music facilitates the fleeting creation of a lesbian space (480).

The creation of this space can happen at the supermarket when lang’s music plays over the speakers, or at one of her concerts where lesbian audience members create this lesbian space through their existence within it. Despite the contemporary understanding of lesbian music as overly earnest and desexualized, what Christina Belcher (2011) calls “shameful lesbian musicality” (413), lesbian music in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s was emotional, sexual, and political, serving as the soundtrack to the social and political awakening of an entire generation of women.

Although women’s music festivals are often depicted as utopic spaces, they are not without their internal issues. In their study of the National Women’s Music Festival, Eder et. al (1994) pose one of the central questions (and one of the central problems) of women’s music festivals. They ask: “Is it possible to create a community based on shared values and identity that is also open to a diverse constituency?” (485). They question whether differences among lesbians can be recognized when the central focus on the festival is the commonality among lesbians. Through their research Eder et. al found that this issue particularly affects lesbians of color, noting that “although they may have felt more welcome as lesbians than in mainstream society, many did not feel accepted as women of color” (501). While many festivals did have specific events, groups, or performances specifically for women of color, criticisms and discussions about lesbian difference were often part of the discourse surrounding these festivals.

The most famous example of inclusion/exclusion at women’s music festivals is tied to the definition of womanhood itself. Apart from Sarah McLachlan’s Lilith Fair, The Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival (MichFest for short) is arguably the most well-known of the women’s music festivals largely because of it’s now (in)famous anti-trans policy. Until it’s closure in 2015, founder Lisa Vogel maintained this policy, despite increasing protests. (This continued backlash was likely one of the reasons for the festival’s discontinuation). In a clear attempt to deflect such criticism, a sample statement from the 25th anniversary of the festival in 2000 reads: “claiming one week a year as womyn-born womyn space is not in contradiction to being trans-positive and trans-allies” (Morris 103). Vogel, as well as Morris herself, seem to indicate that it was the unruly trans activists, rather than transphobic language and exclusion, that shut down the festival and lead to the disappearance of an important cultural movement. It is important to note here that trans exclusion is not necessary for the creation of a successful and safe space for women; there are in fact plenty of other women’s music festivals that did not and do not participate in this exclusion, including the still-running National Women’s Music Festival.

Though trans exclusion in lesbian spaces is not unique to the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, it is unfortunate that MichFest’s policy has come to symbolize what many perceive as the antiquated nature of lesbian culture. As Dolan puts it, “the history that’s been told of women’s culture has been oversimplified to imply a lack of healthy dissent or resistance from within the ranks” (209). Though racial segregation and trans exclusion were present in some of these lesbian spaces of the 20th century, these practices were not enacted or condoned by all within these communities. Nonetheless, issues of inclusion and exclusion permeate throughout all of recent lesbian history and continue today, and must be taken into account when considering the construction of safe spaces.

Conclusion: Gone Where?

What all of these spaces and movements have in common is the sense that they have all begun to disappear – both literally and in terms of their cultural significance. Apart from their brief resurgence in popularity upon the release of Carol (which was based on the Patricia Highsmith novel The Price of Salt) in 2015, lesbian pulp novels have largely gone extinct, and contemporary queer women’s fandom often revolves around television instead of literature. The disappearance of lesbian bars, feminist bookstores, and women’s music festivals is often seen by an older generation of lesbians as the loss of history as well as the loss of a sense of unity that some believe once existed in these spaces. However, my research suggests that this unity, when it did exist, was often at the expense of a more diverse community. Nonetheless, I find this discourse surrounding the disappearance of these cultural institutions an interesting topic to consider. What I want us to evaluate here is where have these spaces gone? What is the cause of their disappearance? And finally, what does all of this have to do with queer women’s culture today?

In her book The Disappearing L, Bonnie Morris attempts to work out some of the reasons why lesbian culture and history seems to have been largely erased. In her own words:

For lesbians, current reasons for cultural erasure include a potent mix of conventional sexism, cycles of conflict where women are set up to attack one another (the old “horizontal hostility” within minority culture), lack of representation in history institutions such as museums, and the mainstreaming of the LGBT movement (178).

This reasoning has some merit, and her note about the lack of institutionalized representations of our history is extremely significant and deserves further consideration. However, Morris goes on to suggest that lesbian culture has gone the way of the dinosaurs because of the contemporary push to include trans people in our spaces and acknowledge them in our histories. As she puts it, “today, “man hating” has been replaced by the label of transphobia or TERF (“Trans Excluding Radical Feminist”) as a means to discredit lesbians and/or deny a platform for articulating lived lesbian experiences” (183). By referring to the term TERF as a “slur” (3), Morris denies the validity of the critiques that trans people and their allies have lobbied at lesbian spaces and histories that exclude trans people, blaming these activists for a “retroactive stigma” (3) that she argues is now applied to events like the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival. Morris is correct in suggesting that “lesbian” is still often seen as a dirty word, but placing the blame for this on the shoulders of trans activists is dishonest and ignores the larger forces at play, including actual forces of sexism, lesbophobia, and biphobia that are still present today.

Unfortunately, Morris is not alone in this opinion that “trans inclusion” is destroying the lesbian community. After all of its original staff were fired in 2016, the once-beloved queer women’s website AfterEllen has now devolved into a space where anti-trans sentiment runs rampant. (Read former AfterEllen writer Heather Hogan’s post about the weaponization of the term “lesbophobia” here). Fortunately, other prominent LGBT women’s media outlets and writers have banded together to fight this regressive movement, and AfterEllen has been swiftly denounced by many others. Sadly, this backward-facing turn by AfterEllen reinforces the perception the lesbian of as a figure of the past – what Elizabeth Freeman calls the “lesbian drag” (Belcher 412). As Belcher puts it, “in other words, the “lesbian” is a temporal figure that pulls the queer, progressive present back toward a degraded, conservative past” (412). The AfterEllen takeover thus contributes to this flattening of what a lesbian is and can be, and ignore the potential for solidarity and community among lesbian, bisexual, queer, and trans people.

Clearly, some of the cultural connotations and spacial boundaries of lesbian culture of the 20th century are still relevant today. As I will illustrate in Chapter 3, ClexaCon is not a perfect space either, as the idea of safety has different connotations for different members of the queer community. Additionally, online spaces can also participate in exclusionary practices. However, there are also some significant differences between queer women’s culture of the past and the present, namely as it relates to the concept of space. For younger queer women, the process of coming out and coming into the queer community is achieved online, whereas older women often came of age by accessing the “network of physical social spaces and events” (Morris 114) that defined lesbian culture from the 1970s to the 1990s. While older queer women might have found self-awareness or self-acceptance through attending one of these events, many younger queer women have this experience after consuming a piece of personally significant media. (Most younger queer women can probably tell you what their first introduction to queer women in the media was – mine was the Pretty Little Liars books).

These significant media moments don’t often lead queer women to the door of a lesbian bar – instead one’s first foray into queer women’s culture might be on Tumblr, Twitter, or YouTube, likely through engagement with a particular fandom. This leads me to an important point about the concept of space. Space can be both physical or virtual – both types of space have the ability to transmit affect, or emotion, through the individuals that travel through and within that space. Thus, while watching Cris Williamson perform at the National Women’s Music Festival in 1975 with 6,000 other women might be a different experience than live-blogging a fictional lesbian couple’s first kiss on Tumblr along with other queer fans, both have the effect of binding these communities together through fandom and through the unifying process of experiencing strong emotions within a group. While these lesbian histories may seem like they come from another world entirely, we can connect them to contemporary cultural productions by highlighting the longstanding centrality of media objects within queer culture, as well as the enduring focus on safe and affirming spaces among communities of queer women. My intent with this chapter was to urge us not to forget these histories, and to suggest that we may celebrate the ways in which these people and these spaces were revolutionary, while also considering some of their downfalls and how these same issues may continue to permeate queer culture today. Now that this history has been uncovered, the next two chapters will focus on queer female community and space as it relates to fandom more specifically.